Home Work

|

| Allison Cooke Brown, Doily Mom, embroidery on vintage doily |

|

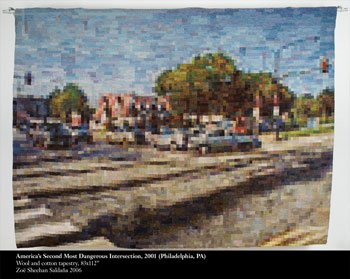

| America's Second Most Dangerous Intersection 2001, (Philadelphia, PA), 2006, wool and cotton tapestry |

|

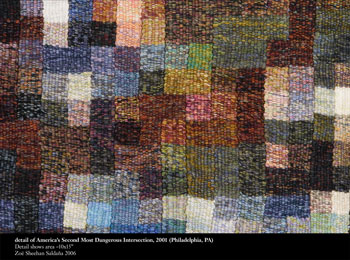

| Zoë Sheehan Saldaña, detail, America's Second Most Dangerous Intersection 2001, (Philadelphia, PA) |

|

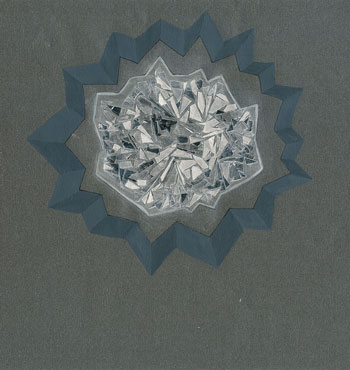

| Sage Lewis, Deconstructed Diamond City |

|

| Sage Lewis, Collage 3, collage on paper |

|

| Alex Sax, Black Cat, cast bronze |

|

| Alex Sax, Chocolate Rabbit, cast bronze |

Despite being trivialized, relegated to confined parlors, and labeled kitsch, craft has happily risen to a spot of prominence in contemporary art-speak. A variety of artists have untethered "women's work" from the humdrum, entering into new aesthetic and conceptual realms. From Judy Chicago and early feminist artists, inspecting and igniting domestic creativity, to contemporary artists such as Michael Raedecker whose sewn paintings express intimacy and longing, sewing is a part of our critical art vocabulary. Whitney Art Works is elated to present four artists, Allison Cooke Brown, Zoë Sheehan Saldaña, Sage Lewis, and Alex Sax, whose use of sewing and needlework represents a smorgasbord of attitudes.

Allison Cooke Brown’s work is most traditional looking… lacy, delicate samplers, and linens covered in fine hand embroidery sweetly convey a decidedly unsweet message. Often her pieces defy the conventions of femininity that Brown grew up with: sayings, standards, and unwarranted advice. For this body of work on display in October, Brown embroidered tattoo designs on delicate vintage hankies. The process required Brown to enter an entirely different world than she was accustomed to. Soliciting designs from tattooists throughout New England, Brown watched tattoos being needled into the skin, and talked at length with those in tattoo shops. As an artist who breaks down the conventions of female behavior, a role that she examines from the inside out, the tattoo designs represent a more unfamiliar community. Though on new ground, Brown’s primary aim is to still investigate the inherent relationship between society and subculture and the comfortable narrowness of pleasant obedience. She describes this project as “ my way of “acting out” from a “proper” New England upbringing.” Indeed Brown’s work has the spirit of a conservatively dressed woman who lifts her dowdy skirt to reveal a pistol in her garter.

Zoë Sheehan Saldaña’s work begins with the simple and logical analogy of pixel to stitch. Beginning in the overabundant cyber world of images (of caliber both crappy and meaningful but mostly crappy), Sheehan delves into a compulsive process of duplication. For example, dangerous intersections throughout the US are portrayed through tapestry in extreme pixilation. The surveillance sources reveal little about what deems these crossroads dangerous. Although the places seem arbitrary and bland, in lush tapestry the effect is wittily complicated. The most interesting thing about Sheehan's work is whether or not she is recontextualizing her material or letting it remain provocatively substance-less. The images are out of focus, but instead of lacking clarity they become objective and objectified. The oblique lens of needlecraft, where the image loses any guise of reality, makes the viewer consider their feelings of dissolution and disinterest. In Sheehan's work the tenderness and physical depth of the carpet-like surface plays counterpoint to the superficial image, a backbone against which these juxtapositions can rest. A faithful maker of all things, Sheehan is known for copying everyday objects, growing things, reproducing cheap items purchased at big box stores and then returning these reproductions. Clearly, Sheehan is engaged with how the automatic and the manual interact in real life and how the artist functions as a quirky machine, obsessive, equivocal, funny and wicked.

Sage Lewis draws, prints, constructs and sews architectural forms and other designs based on logic. Her installation at Whitney Art Works culls inspiration from the Quebec Bridge, a major engineering feat that claimed many lives over the two decades it took to complete. The iron from the bridge’s first incarnation (collapsed) purportedly was used to fashion Iron Rings for early 20th century Canadian engineers. The chaos and destruction in the history of such a lauded construction is channeled in Lewis’s own creations: a combination of careful engineering and incredible, almost flamboyant fragility. Another inspiration is the decorative, art-Deco architecture of diamonds and the related use of Dazzle Camouflage painting by US and British navies during World War I. This technique utilized visual chaos (based on facets) as a way of concealment. Lewis uses such histories and theories as a ring in which to wrestle with ideas of organization and foundation, exploring structural integrity and superfluous design. She says” I’m interested in the structures that support our daily lives—whether it’s an I-beam, a biblical verse, or a law of physics—and what happens when they fall apart.” History as a collection of narratives and documents is seemingly immutable but its subjectivity and gaps in focus make it as biased and imperfect as any artist’s works. Lewis work is literate and methodical but also emotional. It balances the delicate and decorative, the masculine and the feminine, and the strong and logical in a subtle way that is visually pleasing.

Alex Sax uses sewing as a means to bring animals to life. Her project for the last several years, entitled Menagerie Recovery, expresses a fictionalized history through collections of cast paper and bronze animals. “Inspired by the tradition of the traveling menagerie - collections of exotic animals displayed throughout Europe and the United States in the 17th, 18th, and early 20th centuries - each of my menageries is connected to a specific historical figure, with the animals representing aspects of that person’s accomplishments and significance. The animals are presented as recently recovered, rare and endangered species, remnants of the bygone era that predated the modern zoological garden”. This current menagerie is inspired by the life of Gertrude Jekyll, a late 19th century British gardener who turned to horticulture after her eyesight prevented her from painting turning her attention towards nurturing fantastical gardens. Sax will create a nearly real menagerie, in the spirit of Gertrude Jekyll, for Whitney Art Works. Expect flowers patterning the walls, many animals, perhaps fascinated children, and if you are lucky, a scone. Sax’s animals, supported in this show by images and texts about their imagined lives, begin as soft stuffed animals. Sax sews them into the world, as pudgy, squishy creatures only later casting an exoskeleton in paper and sometimes bronze. This maternal first step influences the emotional read of the animals—soft, melancholy, and gentle. The animal's countenances reflect this imperfect and loving process that challenges history to be reenacted and honored in the most vibrant way possible.

-Celeste Parke

Home Work will be on view at Whitney Art Works from October 2nd - 31st. A reception will be held on First Friday October 2nd from 5- 8 pm.

Gallery hours are Wednesday - Saturday from noon- 6pm or by appointment.

© Whitney Art Works, All Rights Reserved. 45 York Street, Portland, Maine 04101 Voice: 207-780-0700

You are viewing the printer-friendly version of Home Work