Kingdom

|

|

|

|

We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals... In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth." -- Henry Beston

Talking about the animal world as a Kingdom, we don’t think of how this serpentine word is securely cemented in the quicksand of human perspective. Be it taxonomical or peaceable, a kingdom is an enclosure for the serfs of man, a biological crowbar between us and them, or a key to the encompassing salvation of the savage and troubled world by Christ. Kingdoms of course, need someone at the top, i.e., its man’s kingdom, His Kingdom, the lion’s kingdom, or the kingdom of the scientist in his tower. So…on the surface this is a show about animals: Andy Rosen's striking fox, Lisa Pixley's hunters and the hunted, Ed Smith's straining mobs of birds, and Justin Richel's tangles of animals living in the coifs of founding fathers. But with deeper consideration, the motives of these artists go beyond biological admiration. They examine struggle and hierarchy. The animals inhabiting the gallery are not fetishes for the artist's spirituality, they are self possessing, activated and muscular. Each artist goes well beyond the dispassionate observations of John James Audubon whose delicate drawings of birds, though some of the first and most thorough wildlife depictions, have a deadness about them. Kingdom is much more about the phenomenon of take over and transformation and the symbiosis of animal and man.

Andy Rosen is a sculptor of agitated yet whimsical characters and environments. Complete but never fussy, his scenes feel as if they were created as some necessary solution or escape. The patient care and fumbling urgency represent, in his words "worry and wonder". For Kingdom, Rosen will contribute a fox on stilts balanced in the center of the gallery. More finely hewn than his previous critters, this fox is as cunning as the stereotype suggests. He skulks up high on dark stilts made by human hands. The precariousness of his situation is ambiguous. Has this fox increased his visibility and power or has he subjected himself to danger by being on these stilts? And did he adapt to these bizarre contraptions himself or was he forced to? And ultimately is anthropomorphism condescension or empathy? Does Beatrix Potter’s fox character Mr. Tod serve to remind children to resist their animal tendencies or does he allow them to draw connections between animal and human behavior, increasing their compassion?

Ed Smith precognitively conveys the stickiness of swampy bird life in his home, Louisiana, where crude from the recent BP oil fiasco has threatened to poison marshes with sludge. Birds bind together and as in Rosen’s piece, the viewer is left to wonder whether they have decided to cope this way of their own accord or whether some adherent is catching them like flies on flypaper. Birds collectively pull themselves along, invisibly burdened. Big pearly buds/growths/oozes appear on the limbs of trees, bright green drops fall from the sky. Smith's work is environmental in a way that has become far more literal in the past months; photos of oily birds seen in newspapers and online inevitably lend the work a nightmare quality. The viewer is captivated by Smith’s elegant compositions, the graceful angles made by curving necks and beaks, the Baroque beauty of the dramatic lighting and the sense of movement, symmetry and control. Yet the acid hues and the eerie stillness despite the swarms is open to wonder and a creeping gravity.

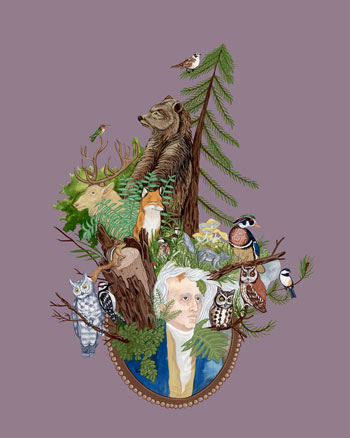

Justin Richel’s gouache paintings of “Big Wigs” depict powerful men shouldered with voluminous wigs so vacuously puffed that they have become infested with flocks of birds and woodland hordes. If you don’t use it you lose it! Richel takes on the complacency of power with the unfettered growth of the natural world that encroaches when self-satisfaction has rendered his “Big wig” guys utterly immobile. The monoliths these men make of themselves with their ostentatious consumption and pompous airs and hairdos make them prime targets for new life. At once satirical and humorously hopeful, Richel shows the immutability of human thought at its worst and in its stead the triumphant reformation and renovation of animals and plants. The men become ornamental stands for a rich and beautiful bevy of life forms.

Another artist who uses the decorative as a subversive force is Lisa Pixley. A rouge of a printmaker, Pixley exploits the high contrast, bold look that is only achievable under the extreme pressure of a printing press, to create a strong undercurrent to the delicate visual feast she provides. It's as if the grinding pressure of the press is evident in the effect of the work. The subjects: game fowl, a hunting dog, a porcupine and an ominous ax are flattened into deep black and white. Everything is life-sized and indelibly suspended in sterile white paper starkly framed in dark wood with insets of strong color. This lack of context around her feathered forms increases the trapped and ornamental effect. Looking like pheasants but consisting only of feathers and small central wounds/orifices, and no heads or feet, these birds are no longer are animals. They are presented to the viewer like gorgeous centerpieces, lacquered with color, arranged to stiffly resemble life. The hunting dog is frozen in the middle of a great leap. His body is at once terrifying and emasculated, solid but held inert. The question of power is key in Pixley's work. Who in the array of her characters is victim and who is perpetrator? And the duplicitous viewer who relishes the sumptuous detail and color in these works, are they to be blamed for their shamefully robust appetites? Pixley, with her fellow artists, invites us to indulge in our human instinct to embellish and enjoy but asks us to complete this activity with sensitivity and skepticism.

-Celeste Parke

Kingdom is one view July 2 - 31.

An opening will be held during the First Friday Art Walk, July 2, from 5-8pm.

An artist talk will be held July 10, at 5 pm!

Whitney Art Works in open Wed - Sat from 12- 6 pm or by appointment.

© Whitney Art Works, All Rights Reserved. 45 York Street, Portland, Maine 04101 Voice: 207-780-0700

You are viewing the printer-friendly version of Kingdom